What is the danger of asking customers what they want?

There's an old episode of The Simpsons where Homer discovers he has a half-brother named Herb Powell.

Herb is the CEO of a car company called Powell Motors, and he's frustrated by his design team's uninspiring new car concepts. So he enlists Homer to help design his company's next car, believing that Homer personifies the wants and needs of the average American consumer.

The result is a disaster. The car, dubbed The Homer, is so overloaded with unnecessary features that it can't be sold at a profit.

There's a real-life lesson here. Customers have diverse tastes and interests. And a customer merely wanting something doesn't automatically mean a company can make money providing it.

I’m a huge fan of the online pet store, Chewy. It offers convenient online ordering, a huge selection of products, incredible prices, and has a fun and helpful service culture. Chewy’s sales have grown rapidly over the past several years, but the retailer has yet to turn a profit.

At The Overlook, a vacation rental cabin my wife and I own, we've gotten all sorts of requests. A few have asked for air conditioning, which would be cost-prohibitive to install given the short warm period of the year is also a slow time. Others suggested we list The Overlook on Airbnb, but the listing fees would add expense without bringing in much additional revenue. (Airbnb would also make The Overlook more expensive for our guests.)

Sometimes different groups of customers have conflicting needs. For example, all the rooms at The Overlook have either a king or a queen bed. This is perfect for our target market, but others would prefer bunk beds, sleeper sofas, and air mattresses to accommodate as many people as possible in one house.

When I researched customer-focused organizations while writing The Service Culture Handbook, I consistently found these companies resisted the urge to be all things to all people. That’s why you won’t find a chicken salad on the menu at In-N-Out Burger, but you will find a line of loyal customers waiting to get their hands on a delicious cheeseburger at 10pm on a Wednesday evening.

Who should help write your vision?

The vision should be rooted in reality. It should describe how you’d like to serve customers in the future based on how you serve customers today when everything is going well. For this reason, all employees should be given a chance to provide input on your customer service vision.

This step-by-step guide describes how to do that.

When it comes to drafting the vision statement, there should only be 7-10 people in the room, plus an outside facilitator if you decide to use one. More than that, and the group becomes unwieldy. Fewer than that, and not enough perspectives are included.

The group should be comprised of a representative sample of employees:

At least one frontline employee. They keep it real.

At least one senior leader. They provide authority.

At least one mid-level manager or supervisor. They're the link between execs and the front lines.

Many organizations try to have the executive team create the customer service vision at a retreat. My research reveals that's a big mistake.

Should you ever ask customers about your vision?

Absolutely!

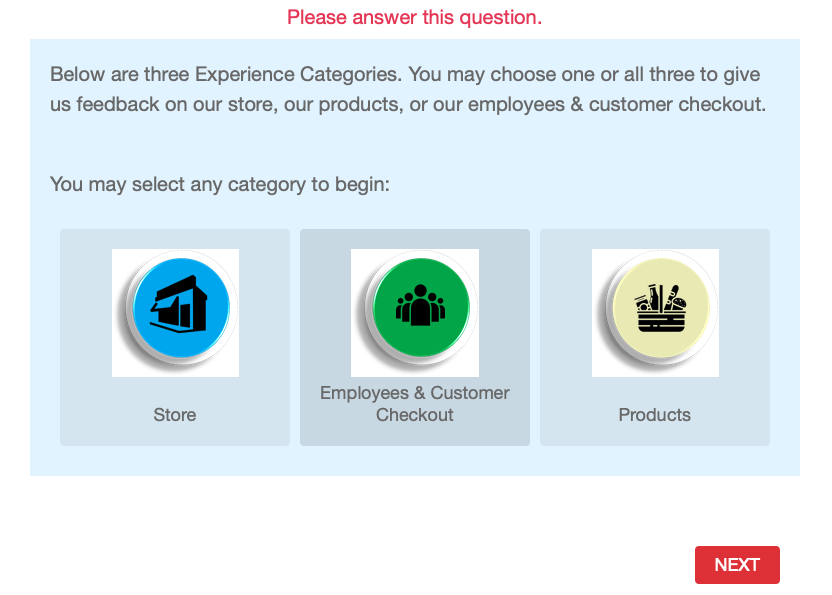

The time to ask customers for their input is after you write the vision and start using it to guide your operations. This is when customer feedback can be invaluable. Keep in mind you're not asking customers what they want, you're asking them how well you are executing your vision.

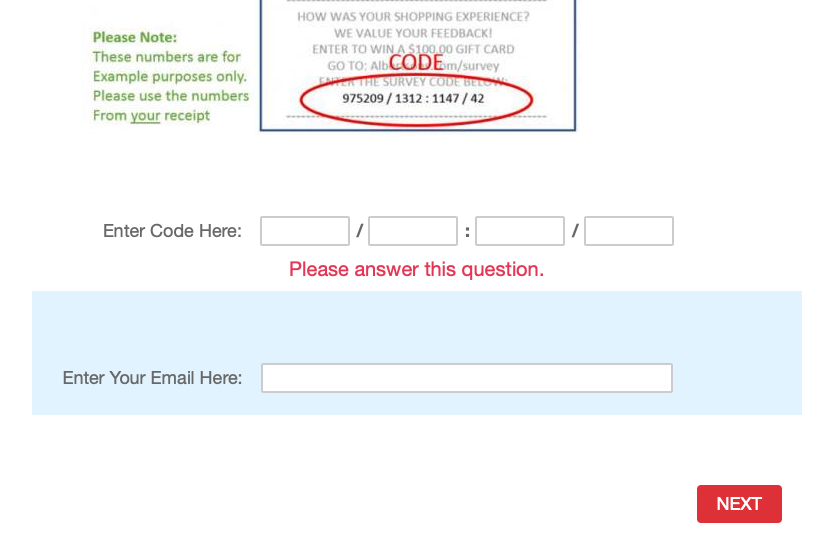

At The Overlook, our vision is welcome to your mountain retreat. We constantly use guest feedback from surveys, comments, and even our own observations, to refine our approach. For example, we added extra guest towels after learning that many guests like to shower after returning from a sweaty hike, but don’t want to use the same towel later that evening when they use the hot tub.

How can I write a vision statement?

Here are some resources that can help you write an effective customer service vision: